What happens when the sun eats a comet?

What happens when the sun eats a comet? It gets terrible solar gas.

No one can blame us for thinking the question sounds like a joke. After all, the sun doesn’t actually “eat” a comet, but it can pretty much consume it and, on occasion, “burp” it out. And as you’ll see, our punch line is more serious than you’d think.

When you see a picture of a comet in the sky, you’re generally seeing a glowing ball followed by an ethereal-looking trail of gas. The center of the comet (or the nucleus) is made up of rock, gravel and ice. And that nucleus can be less substantial than you’d think, if you’re judging it based on the comet’s gigantic coma (the glowing ball that surrounds the nucleus and consists of gas). For instance, when the comet Ison passed by the sun in 2013, its nucleus was only about 1.2 miles (2 kilometers) across [source: Plait]. Even with the relatively small nucleus (compared, say, to Hale-Bopp’s 1997’s appearance, with its roughly 20-mile, or 32-kilometer, nucleus), Ison still had a whopping 80,000-mile (120,000-kilometer) coma. And that’s not even taking into account its 5 million-mile (8 million-kilometer) tail [source: Plait].

Just like planets, comets orbit the sun. And some of those comets come super close to it: They’re called “sungrazers” because their path allows them to get all up in the sun’s business. Since the sun is a star and not a rocky planet like Earth, it doesn’t have a hard core for the comet to hit, as it’s only composed of gas. What does that mean when a comet gets too near it?

There are a few possibilities. One is that the comet makes the flyby successfully; its nucleus withstands the heat and it survives the trip. (Keep in mind it disintegrates eventually on its orbit anyway, as the sun evaporates the ice of its nucleus.) Another possibility is that the comet approaches the sun but disintegrates before it can hit it. Lastly, it may emerge on the other side (and perhaps put on a fantastic light show as it does).

Let’s get a little closer to the heat, and see what happens when a comet gets caught in the sun’s web.

So what actually happens when a sungrazer comet decides to cool off with a plunge into the sun? The answer might be vaguely unsatisfying. Because what happens is generally what happens to a comet that doesn’t hit the sun: It disintegrates into nothingness, as its icy, gravel nucleus proves no match for the sun’s heat.

You might be surprised to hear that, because when a sungrazer makes the news, it’s usually accompanied by screaming headlines going on about “comets hitting the sun,” followed by a breathless recounting of “fiery explosions.” While this is what you might think you see from videos of the occurrences, don’t make too many assumptions.

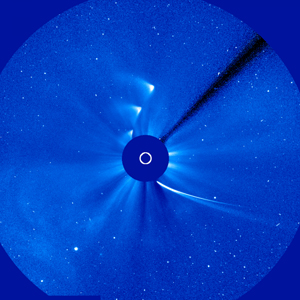

What you’re looking at are coronal mass ejections — huge explosions of gas and magnetic energy that disrupt the solar wind (see: punch line to joke) [source: Hathaway]. And yes, we do occasionally see them emanating from the sun after comets make their way into the sun’s pull. But there’s no proof that the comet actually is causing the explosion; coronal mass ejections are seen often and it’s hard to say that comets are causing them [source: Plait]. It’s also important to note that comets have blasted into the sun with no resulting coronal mass ejections.

Which brings us to the important point that every comet is different. It’s hard to say what will happen each time one approaches the sun. In 2013, the comet Ison was one example of unpredictability: While its nucleus appeared to break apart from the heat, at least some part of it seems to have survived the trip [source: Plait].

But don’t feel totally let down about a comet’s display. No, we might not see unusual explosions in the sky, but a comet that approaches the sun always leaves the possibility for a great show. That’s because when the comet gets to the point where it’s closest to the sun (known as perihelion), its solid state will sublimate and turn straight into a gaseous state. When that happens, the comet can brighten considerably, making a vivid sight in the sky [source: Rincon].

Creators of mankind

Creators of mankind Description of “Tall white aliens”

Description of “Tall white aliens” Where they came from?

Where they came from? About hostile civilizations

About hostile civilizations The war for the Earth

The war for the Earth “Tall white aliens” about eternal life

“Tall white aliens” about eternal life Video: “Nordic aliens”

Video: “Nordic aliens” Aliens

Aliens Alien encounters

Alien encounters The aliens base

The aliens base UFO

UFO Technology UFO

Technology UFO Underground civilization

Underground civilization Ancient alien artifacts

Ancient alien artifacts Military and UFO

Military and UFO Mysteries and hypotheses

Mysteries and hypotheses Scientific facts

Scientific facts