How NASA Planetary Protection Works

n 1972, the Apollo 16 mission returned to Earth with 731 rock and soil samples taken from the lunar central highlands, which they eventually sent to labs around the world. One of those labs was buried beneath Area 51, the top-secret military installation located in southern Nevada. There, a team of geologists and astrobiologists recovered spores of unknown origin from a rock’s surface and stored the reproductive structures for further study.

The peculiar spores remained dormant until 1974, when they suddenly germinated, infecting dozens of lab workers and producing symptoms similar to those caused by the Ebola virus. The outbreak, known as the Crenshaw Episode after the first person to contract the mysterious illness, claimed seven lives until lab authorities could contain the microbes and prevent further infection.

Now the good news: We lied. The preceding story, at least the part about the Crenshaw Episode, is a complete fabrication. And the bad news: It’s based on events that really could happen.

In fact, NASA created the Planetary Protection Office in the 1960s to consider scenarios just like these. Seriously? NASA really spends hard-earned taxpayer money to study extraterrestrial bugs? You bet. And it’s not just because agency officials fret over a lunar or Martian microbe wiping out Earth’s population. They’re also worried about what our germs could do if they gained a toehold on another planet. A few transplanted bacteria might confound future searches for life or, worse, kill any indigenous organisms.

Yes, sir, humans have been mulling over this issue for decades. By the time John F. Kennedy delivered his “we choose to go to the moon” speech in 1962, scientists had already discussed the issue in September 1956, when the International Astronautical Federation convened its seventh congress in Rome.

Almost exactly a year later, the Soviet Union launched Sputnik, ushering in the space race and moving the concept of lunar and planetary contamination from a vague possibility to a sudden and frightening reality.

Although astronomers and astrobiologists discussed planetary protection as early as 1956, they didn’t really mobilize until 1958. In the spring of that momentous year, the National Academy of Sciences created the Space Science Board to study the scientific aspects of the human exploration of space.

By June, the academy, based on the board’s recommendations, shared its concerns about contamination with the International Congress of Scientific Unions (ICSU), hoping to make the issue a global concern. What did the ICSU do? Form a committee on Contamination by Extraterrestrial Exploration (CETEX) to evaluate whether human exploration of the moon, Venus and Mars could lead to contamination. The CETEX folks reasoned that terrestrial microorganisms would have little hope of surviving on the moon, but that they might be able to eke out an existence on Mars or Venus. As a result, CETEX recommended that humans send only sterilized space vehicles, including orbiters that could have accidental impacts, to those planets.

By the fall of 1958, the ICSU decided it was time to form yet another planetary protection committee. This one, known as the Committee on Space Research, or COSPAR, eventually came to oversee the biological aspects of interplanetary exploration, including spacecraft sterilization and planetary quarantine. COSPAR replaced CETEX. Got that?

At the same time, NASA was being born in the United States. In 1959, Abe Silverstein, NASA’s director of Space Flight Programs, made the U.S. space agency’s first formal statements about planetary protection:

The National Aeronautics and Space Administration has been considering the problem of sterilization of payloads that might impact a celestial body. … As a result of the deliberations, it has been established as a NASA policy that payloads which might impact a celestial body must be sterilized before launching.

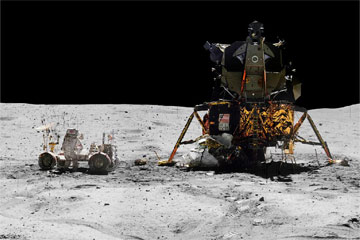

That same year, planetary protection responsibilities bounced around within NASA like an orphaned child. They were delegated first to the Office of Life Sciences and then to the Office of Space Science and Applications. In 1963, within that office’s Biosciences Programs, the Planetary Quarantine Program began and eventually oversaw several Apollo mission activities, such as shielding moon rocks from terrestrial contamination and protecting Earth from lunar wee beasties, if they existed.

In 1976, the Planetary Quarantine Program became the Office of Planetary Protection, and the PQ Officer became the Planetary Protection Officer (PPO). Today, the PPO is still a major player when it comes to shaping NASA missions. He or she consults with internal and external advisory committees and then provides guidance on, well, just about everything, from how a spacecraft must be assembled to how samples from other celestial bodies are collected, stored and returned to Earth.

As you can imagine, the mission teams don’t always love the PPO because his or her recommendations make their jobs harder. But then again, who cares? The PPO has a very profound — and a profoundly difficult — task, which is to protect life in the galaxy at all costs.

Creators of mankind

Creators of mankind Description of “Tall white aliens”

Description of “Tall white aliens” Where they came from?

Where they came from? About hostile civilizations

About hostile civilizations The war for the Earth

The war for the Earth “Tall white aliens” about eternal life

“Tall white aliens” about eternal life Video: “Nordic aliens”

Video: “Nordic aliens” Aliens

Aliens Alien encounters

Alien encounters The aliens base

The aliens base UFO

UFO Technology UFO

Technology UFO Underground civilization

Underground civilization Ancient alien artifacts

Ancient alien artifacts Military and UFO

Military and UFO Mysteries and hypotheses

Mysteries and hypotheses Scientific facts

Scientific facts