New DNA Testing on 2,000-Year-Old Elongated Paracas Skulls Changes Known History

The elongated skulls of Paracas in Peru caused a stir in 2014 when a geneticist that carried out preliminary DNA testing reported that they have mitochondrial DNA “with mutations unknown in any human, primate, or animal known so far”. Now a second round of DNA testing has been completed and the results are just as controversial – the skulls tested, which date back as far as 2,000 years, were shown to have European and Middle Eastern Origin. These surprising results change the known history about how the Americas were populated.

Paracas is a desert peninsula located within Pisco Province on the south coast of Peru. It is here where Peruvian archaeologist, Julio Tello, made an amazing discovery in 1928 – a massive and elaborate graveyard containing tombs filled with the remains of individuals with the largest elongated skulls found anywhere in the world. These have come to be known as the ‘ Paracas skulls ’. In total, Tello found more than 300 of these elongated skulls, some of which date back around 3,000 years.

Elongated skulls on display at Museo Regional de Ica in the city of Ica in Peru ( public domain )

Strange Features of the Paracas Skulls

It is well-known that most cases of skull elongation are the result of cranial deformation, head flattening, or head binding, in which the skull is intentionally deformed by applying force over a long period of time. It is usually achieved by binding the head between two pieces of wood, or binding in cloth. However, while cranial deformation changes the shape of the skull, it does not alter other features that are characteristic of a regular human skull.

In a recent interview with Ancient Origins, author and researcher LA Marzulli describes how some of the Paracas skulls are different to ordinary human skulls:

“There is a possibility that it might have been cradle headboarded, but the reason why I don’t think so is because the position of the foramen magnum is back towards the rear of the skull. A normal foramen magnum would be closer to the jaw line…”

LA Marzulli points to the position of the foramen magnum in a Paracas skull which is also the point at which they drilled in order to extract bone powder for DNA testing.

Marzulli explained that an archaeologist has written a paper about his study of the position of the foramen magnum in over 1000 skulls. “He states that the Paracas skulls, the position of the foramen magnum is completely different than a normal human being, it is also smaller, which lends itself to our theory that this is not cradle headboarding, this is genetic.”

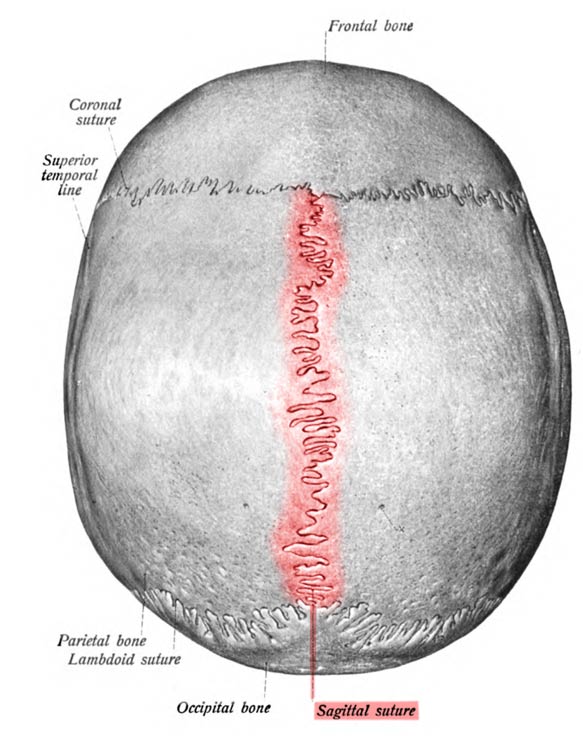

In addition, Marzulli described how some of the Paracas skulls have a very pronounced zygomatic arch (cheek bone), different eye sockets and no sagittal suture, which is a connective tissue joint between the two parietal bones of the skull.

The pronounced cheek bones can be seen in artist Marcia Moore’s interpretation of how the Paracas people looked based on a digital reconstruction from the skulls. Marcia Moore / Ciamar Studio

In a normal human skull, there should be a suture which goes from the frontal plate … clear over the dome of the skull separating the parietal plates – the two separate plates – and connecting with the occipital plate in the rear,” said Marzulli. “We see many skulls in Paracas that are completely devoid of a sagittal suture.

There is a disease known as craniosynostosis, which results in the fusing together of the two parietal plates, however, Marzulli said there is no evidence of this disease in the Paracas skulls.

The sagittal suture, highlighted in red, separates the two parietal plates ( public domain )

LA Marzulli shows the top of one of the Paracas skulls, which has no sagittal suture.

DNA Testing

The late Sr. Juan Navarro, owner and director of the Museo Arqueologico Paracas, which houses a collection of 35 of the Paracas skulls, allowed the taking of samples from three of the elongated skulls for DNA testing, including one infant. Another sample was obtained from a Peruvian skull that had been in the US for 75 years. One of the skulls was dated to around 2,000 years old, while another was 800 years old.

The samples consisted of hair and bone powder, which was extracted by drilling deeply into the foramen magnum. This process, Marzulli explained, is to reduce the risk of contamination. In addition, full protective clothing was worn.

The samples were then sent to three separate labs for testing – one in Canada, and two in the United States. The geneticists were only told that the samples came from an ancient mummy, so as not to create any preconceived ideas.

Creators of mankind

Creators of mankind Description of “Tall white aliens”

Description of “Tall white aliens” Where they came from?

Where they came from? About hostile civilizations

About hostile civilizations The war for the Earth

The war for the Earth “Tall white aliens” about eternal life

“Tall white aliens” about eternal life Video: “Nordic aliens”

Video: “Nordic aliens” Aliens

Aliens Alien encounters

Alien encounters The aliens base

The aliens base UFO

UFO Technology UFO

Technology UFO Underground civilization

Underground civilization Ancient alien artifacts

Ancient alien artifacts Military and UFO

Military and UFO Mysteries and hypotheses

Mysteries and hypotheses Scientific facts

Scientific facts