Scottish storms unearth 1,500-year-old Viking-era cemetery

Powerful storms on the Orkney Islands in the far north of Scotland recently exposed ancient human bones in a Pictish and Viking cemetery dating to almost 1,500 years ago. Volunteers are piling sandbags and clay to protect the remains and limit the damage to the ancient Newark Bay cemetery on Orkney’s largest island.

The cemetery traces its origins to the middle of the sixth century, when the Orkney Islands were inhabited by native Pictish people, akin to the Picts who inhabited most of what is now Scotland.

It was used for almost a thousand years, and many of the burials from the ninth through the 15th centuries were Norsemen or Vikings who had taken over the Orkney Islands from the Picts. But waves raised by storms are eating away at the low cliff where the ancient cemetery lies, said Peter Higgins of the Orkney Research Center for Archaeology (ORCA), part of the Archaeology Institute of the University of the Highlands and Islands.

Related: Fierce fighters: 7 secrets of Viking seamen

“Every time we have a storm with a bit of a south-easterly [wind], it really gets in there and actively erodes what is just soft sandstone,” Higgins told Live Science.

About 250 skeletons were removed from the cemetery about 50 years ago, but it’s not known exactly how far the graveyard extends back from the beach, he said. Hundreds of Pictish and Norse bodies are thought to be buried there still, Higgins added.

The Orkney Islands have been inhabited for thousands of years and have many of the best-preserved archaeological sites in Europe. That includes the prehistoric village of Skara Brae and the standing stones of the Ring of Brodgar, a ceremonial site that includes 13 burial mounds and dates to 3,000 B.C., according to the government agency Historic Environment Scotland (HES).

The ancient cemetery at Newark Bay was excavated in the 1960s and 1970s by the famed British archaeologist Don Brothwell, who preserved the skeletons for future study, Higgins said. Brothwell’s methods were current at the time, but they were very different from modern archaeological techniques, and “the archive isn’t quite the way we’d have it nowadays,” Higgins added. Volunteers now hope to preserve the bones until the remains can be examined by scientists over the next three years, in HES-funded studies.

But a more immediate concern is the vulnerability of the remaining graves to flooding and damage from Orkney storms, which batter the sandstone cliff with enormous waves and storm surges, representatives of the Archaeology Institute said in a statement.

“The local residents and the landowner have been quite concerned about what’s left of the cemetery being eroded by the sea,” Higgins said.

Exposed bones are typically either covered with clay to protect them or removed from the sandstone cliff after their positions are carefully recorded, so it is rare for bones to end up on the beach, he said

It’s not known yet if the exposed bones are those of Picts or Vikings; no burial objects or traces of funeral clothing remain, and bodies in the cemetery were buried four or five layers deep.

Cultural transition

Historians say the first Norse immigrants to the Orkney Islands settled there in the late eighth century, fleeing an emerging new monarchy in Norway. They used the Orkney Islands to launch their own voyages and Viking raids, and eventually, all Orkney was dominated by the Norse, The Scotsman reported. The islands became a Norwegian earldom late in the ninth century, and they remain the region of the British Isles that is most influenced by Norse culture.

Related: Photos: Viking settlement discovered at L’Anse aux Meadows

The relationship between the Picts and the Norse on the Orkney Islands is hotly debated among scholars: Did the Norse take over by force, or were they settlers who traded and intermarried with the Picts? The ancient cemetery at Newark Bay may help to answer that question, Higgins said.

“The Orkney Islands were Pictish, and then they became Norse,” he said. “We’re not really clear how that transition happened, whether it was an invasion or people lived together. This is one of the few opportunities we’ve got to investigate that.”

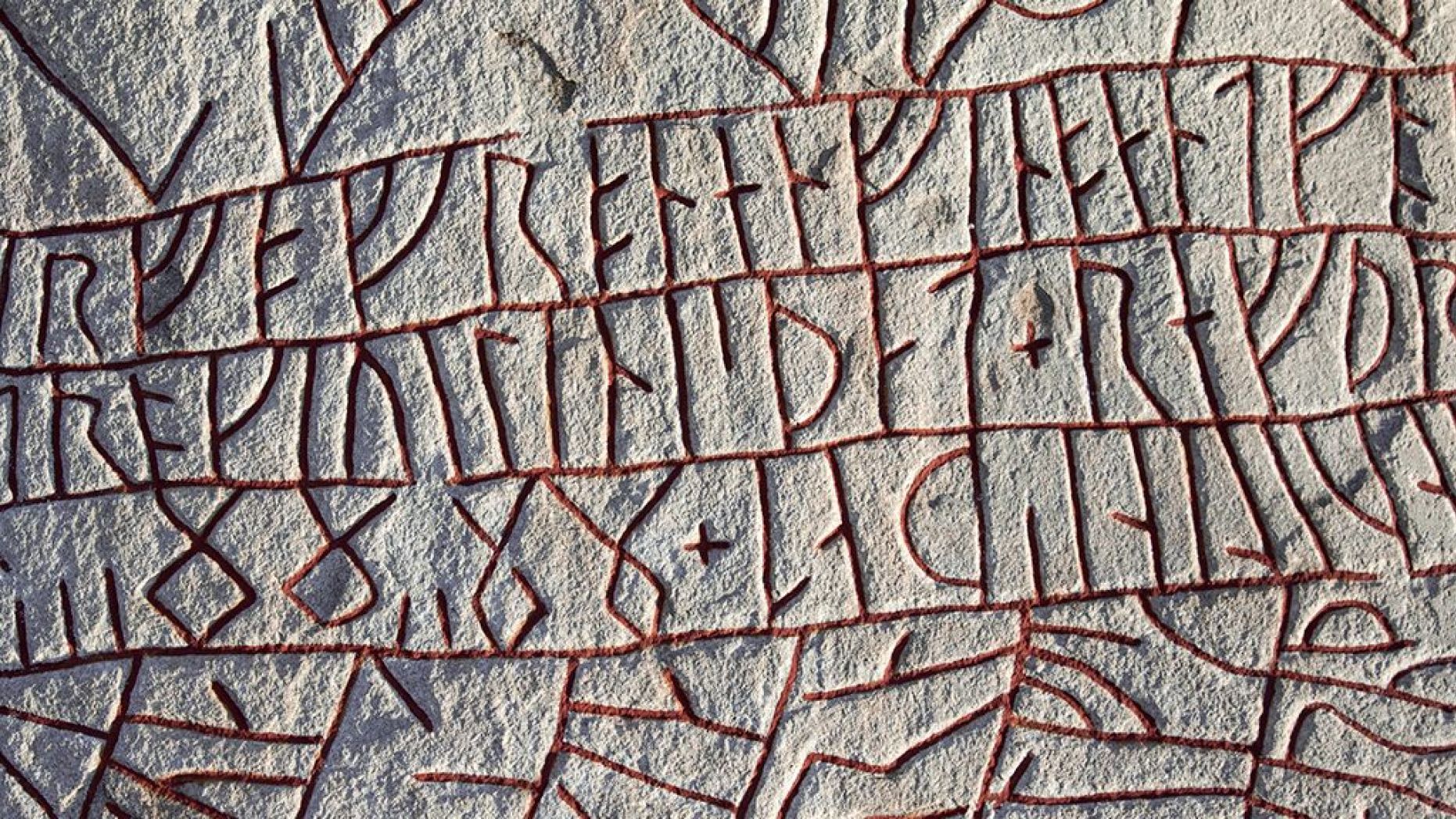

Excavations at the site had unearthed a carved Pictish stone and the buried remains of a medieval Christian chapel. However, some of the graves could be pre-Christian, Higgins said.

Part of the scientific work on the remains would involve testing genetic material from the ancient bones, which might show that some people living on Orkney today are descended from people who lived on the islands over 1,000 years ago.

“We’re fairly confident that we’re going to find that some local residents are related to people in the cemetery,” Higgins said.

Creators of mankind

Creators of mankind Description of “Tall white aliens”

Description of “Tall white aliens” Where they came from?

Where they came from? About hostile civilizations

About hostile civilizations The war for the Earth

The war for the Earth “Tall white aliens” about eternal life

“Tall white aliens” about eternal life Video: “Nordic aliens”

Video: “Nordic aliens” Aliens

Aliens Alien encounters

Alien encounters The aliens base

The aliens base UFO

UFO Technology UFO

Technology UFO Underground civilization

Underground civilization Ancient alien artifacts

Ancient alien artifacts Military and UFO

Military and UFO Mysteries and hypotheses

Mysteries and hypotheses Scientific facts

Scientific facts