Voyager spacecraft sail on, 40 years after launch

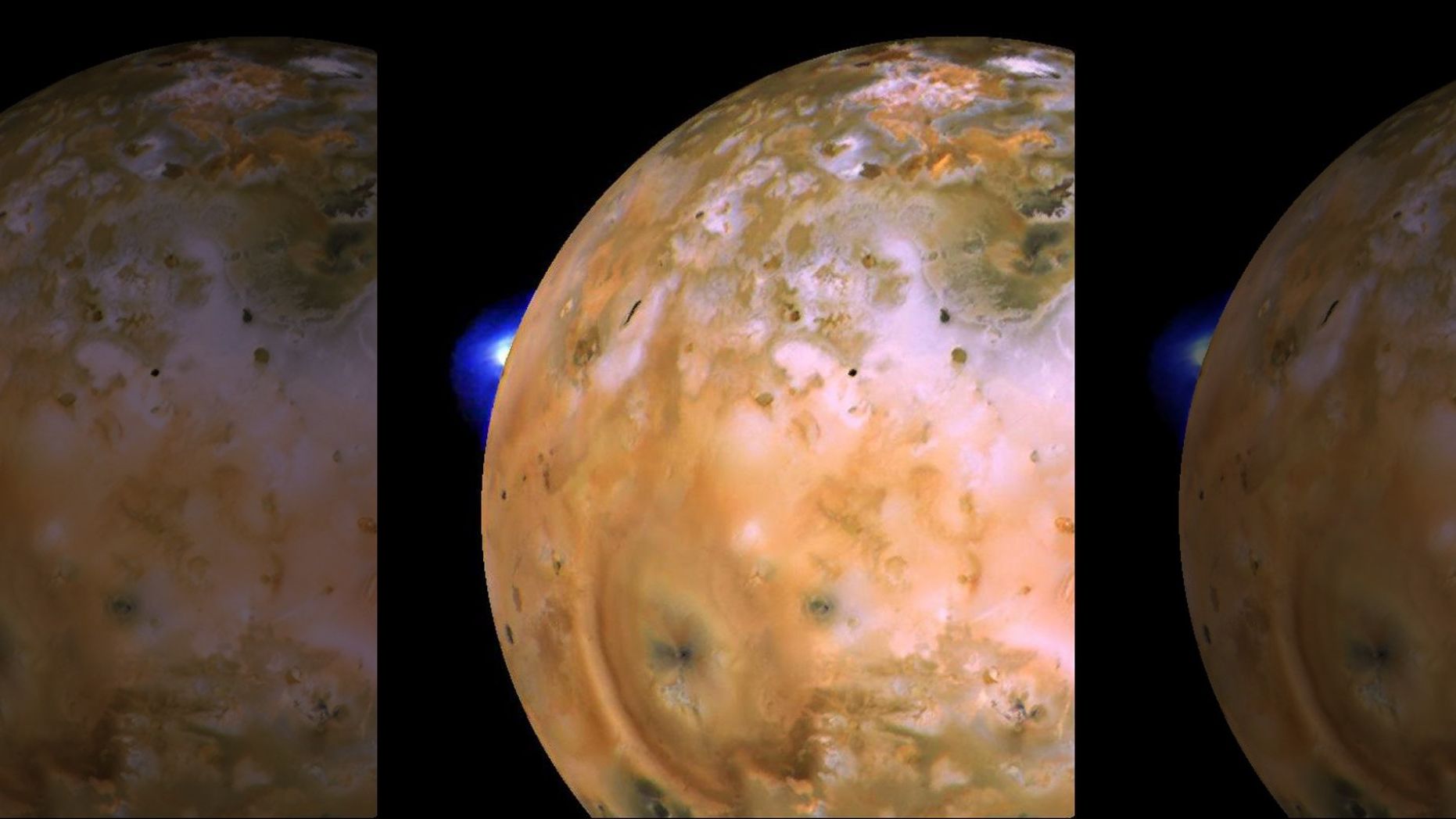

Voyager 1 image of Jupiter’s volcanic moon Io showing the active plume of a volcano called Loki. Th heart-shaped feature southeast of Loki consists of fallout deposits from active plume Pele. The images that make up this mosaic were taken from an average distance of about 340,000 miles (490,000 kilometers).

Nearly 40 years after lifting off, NASA’s historic Voyager mission is still exploring the cosmos.

The twin spacecraft launched several weeks apart in 1977 — Voyager 2 on Aug. 20 and Voyager 1 on Sept. 5 — with an initial goal to explore the outer solar system. Voyager 1 flew by Jupiter and Saturn, while its twin took advantage of an unusual planetary alignment to visit Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus and Neptune.

And then the spacecraft kept on flying, for billions and billions of miles. Both remain active today, beaming data home from previously unexplored realms. Indeed, in August 2012, Voyager 1 became the first human-made object ever to reach interstellar space. [Photos from Voyager 1 and 2’s Grand Tour]

The mission’s legacy reached into film, art and music with the inclusion of a “Golden Record” of Earth messages, sounds and pictures designed to give any prospective alien who encountered it an idea of what humanity and our home planet are like. This time capsule is expected to last billions of years.

More on this…

Voyager mission

Voyager 1

Photos from Voyager 1 and 2’s Grand Tour

Golden Record

“I believe that few missions can ever match the achievements of the Voyager spacecraft during their four decades of exploration,” Thomas Zurbuchen, associate administrator for the Science Mission Directorate at NASA headquarters in Washington, D.C., said in a statement. “They have educated us to the unknown wonders of the universe and truly inspired humanity to continue to explore our solar system and beyond.”

The spacecraft are now flying through space far away from any planet or star; their next close encounter with a cosmic object isn’t expected to occur for 40,000 years. Their observations, however, are giving scientists more insight into where the sun’s influence diminishes in our solar system, and where interstellar space begins.

Voyager 1 is nearly 13 billion miles (21 billion kilometers) from Earth and has spent five years in interstellar space. This zone is not completely empty; it contains material left over from stars that exploded as supernovas millions of years ago. The “interstellar medium” (as the space in this region is called) is not a threat to Voyager 1. Rather, it’s an interesting environment that the spacecraft is studying.

Voyager 1’s observations show that the huge bubble of the sun’s magnetic influence, which is known as the heliosphere, protects Earth and other planets from cosmic radiation. Cosmic rays (atomic nuclei traveling almost at the speed of light) are four times less abundant near Earth than they are in interstellar space, Voyager 1 has found.

Voyager 2 is nearly 11 billion miles (18 billion km) from Earth and will likely enter interstellar space in a few years, NASA officials have said. Its observations from the edge of the solar system help scientists make comparisons between interstellar space and the heliosphere. When Voyager 2 crosses the boundary, the two spacecraft can sample the interstellar medium from two different locations at the same time.

“None of us knew, when we launched 40 years ago, that anything would still be working, and continuing on this pioneering journey,” Ed Stone, Voyager project scientist at the California Institute of Technology in Pasadena, said in the same statement. “The most exciting thing they find in the next five years is likely to be something that we didn’t know was out there to be discovered.”

Mission designers made the spacecraft robust to make sure they could survive the harsh radiation environment at Jupiter. This included so-called redundant systems — meaning the spacecraft can switch to backup systems if needed — and power supplies that have lasted well beyond the spacecraft’s primary mission.

Each of the spacecraft is powered by three radioisotope thermoelectric generators, which convert the heat produced by the radioactive decay of plutonium-238 into electricity. The power available to each Voyager, however, decreases by about 4 watts per year. This requires engineers to dig into 1970s documentation (or to speak with former Voyager personnel) to operate the spacecraft as its power diminishes.

Even with an eye to efficiency, the last science instrument will have to be shut off around 2030, mission team members have said. But even after that, the Voyagers will continue their journey (albeit without gathering data), flying at more than 30,000 mph (48,280 km/h) and orbiting the Milky Way every 225 million years.

In their four decades in space, the spacecraft have set many records and made key discoveries about the outer solar system and interstellar space. These include:

First and only spacecraft to enter interstellar space (Voyager 1).

First and only spacecraft to fly by all four outer planets (Voyager 2).

First active volcanoes seen beyond Earth, on Jupiter’s moon Io (both Voyagers).

Finding evidence of a subsurface ocean on Jupiter’s moon Europa (both Voyagers).

Discovering an early-Earth-like atmosphere on Saturn’s moon Titan (both Voyagers).

Imaging the chaotic terrain of Uranus’ moon Miranda (Voyager 2).

Imaging icy geysers on Neptune’s moon Triton (Voyager 2).

Creators of mankind

Creators of mankind Description of “Tall white aliens”

Description of “Tall white aliens” Where they came from?

Where they came from? About hostile civilizations

About hostile civilizations The war for the Earth

The war for the Earth “Tall white aliens” about eternal life

“Tall white aliens” about eternal life Video: “Nordic aliens”

Video: “Nordic aliens” Aliens

Aliens Alien encounters

Alien encounters The aliens base

The aliens base UFO

UFO Technology UFO

Technology UFO Underground civilization

Underground civilization Ancient alien artifacts

Ancient alien artifacts Military and UFO

Military and UFO Mysteries and hypotheses

Mysteries and hypotheses Scientific facts

Scientific facts