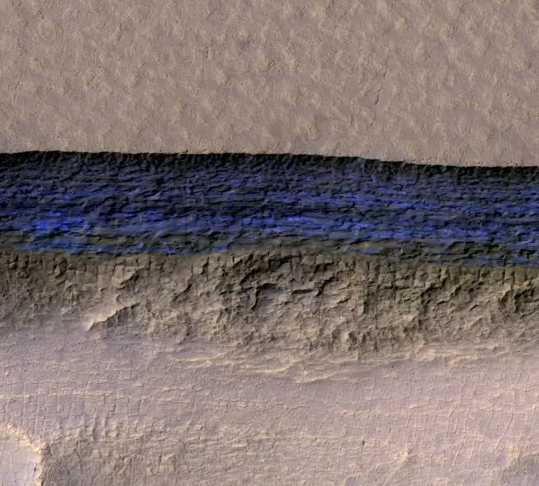

Nasa finds huge sheets of ICE below surface of Mars that could provide water for human settlers

UNDERGROUND ice supplies have been discovered on Mars which could provide unlimited water for humans looking to colonise the Red Planet.

Some of the “pure” frozen sheets are believed to be about 100 meters thick while others are buried just one meter below the dusty surface.

Although scientists knew ice existed on Mars, the new discovery shows just how much of it there is and how accessible it is for astronauts.

The sheer size of the ice sheets could help scientists better understand the history of Mars and its climate, NASA said in a new report.

“Humans need water wherever they go, and it’s very heavy to carry with you,” said Shane Byrne of the University of Arizona Lunar and Planetary Laboratory, Tucson, a co-author of the report.

“Previous ideas for extracting human-usable water from Mars were to pull it from the very dry atmosphere or to break down water-containing rocks. Here we have what we think is almost pure water ice buried just below the surface.

“You can go out with a bucket and shovel and just collect as much water as you need. I think it’s sort of a game-changer.

“It’s also much closer to places humans would probably land as opposed to the polar caps, which are very inhospitable.”

The sites are in both northern and southern hemispheres of Mars, at latitudes from about 55 to 58 degrees, equivalent on Earth to Scotland or the tip of South America.

The remarkable ice cliffs appear to contain distinct layers, which could preserve a record of Mars’ past climate, according to the report.

Scientists say an analysis of the deposits would unleash a treasure trove of information to geologists about the past Martian climate.

“That preserved record would be of extreme importance to go back to,” G. Scott Hubbard, a space scientist at Stanford University in Palo Alto, California told Science.

Creators of mankind

Creators of mankind Description of “Tall white aliens”

Description of “Tall white aliens” Where they came from?

Where they came from? About hostile civilizations

About hostile civilizations The war for the Earth

The war for the Earth “Tall white aliens” about eternal life

“Tall white aliens” about eternal life Video: “Nordic aliens”

Video: “Nordic aliens” Aliens

Aliens Alien encounters

Alien encounters The aliens base

The aliens base UFO

UFO Technology UFO

Technology UFO Underground civilization

Underground civilization Ancient alien artifacts

Ancient alien artifacts Military and UFO

Military and UFO Mysteries and hypotheses

Mysteries and hypotheses Scientific facts

Scientific facts