Are we not the only Earth out there?

You stand in a perpetual sunset, beneath an eerie, reddish-orange sky laced with thin clouds. At the edge of a vast sea, solid ground rises slowly from the water, giving way to lowlands covered in vegetation. The plants bask in temperatures reaching 40 degrees Fahrenheit (4 degrees Celsius), but their leaves aren’t green — they’re black and spread open wide to absorb the scant energy washing across the landscape.

You’ve come to this paradise from your permanent home, an outpost located on the dark, frozen side of the planet. You hike down the lowland hills to the water’s edge. As you gaze at the horizon, you vow that, next year, you’ll bring the whole family so they can enjoy the color and heat and light. Then you realize that next year is just 37 days away, and you feel suddenly small and insignificant in a vast, overwhelming universe.

This could be your future Earth. No, really.

The scene we just described is an artistic interpretation of what Gliese 581g — a potential Earth-like planet discovered in 2010 — might be like if we could travel the 20.5 light-years to get to it. Granted, astronomers haven’t confirmed its existence, but that hasn’t stopped a few from running computer simulations to predict 581g’s climate and overall habitability.

The models suggest that this strangely familiar world, which races around red-dwarf Gliese 581 in just 37 days, keeping one face pointed at the star at all times, may be covered in water and may possess an atmosphere containing large amounts of carbon dioxide. If so, a greenhouse effect just might heat the region directly facing the host star, producing an ice-covered planet with a large area of liquid water in the middle that looks like the iris of an eye. This “eyeball Earth” could support life, including photosynthetic organisms with black pigments especially suited to absorb the weak light filtering through the thick atmosphere.

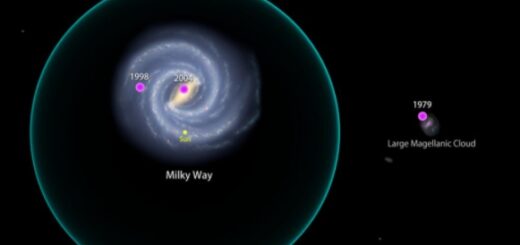

Even if Gliese 581g turns out to be a figment of astronomy’s imagination, it stands as a symbol of what could be humanity’s greatest triumph: finding a habitable planet outside of our solar system. A few years ago, this seemed a dream of fools and sci-fi fanatics. Now, thanks to advanced planet-hunting techniques and some serious equipment, such as the Kepler space telescope, astronomers are locating thousands of candidate planets outside of our solar system — what they call exoplanets — and are coming to a sobering, almost frightening realization: The universe may be filled with billions of planets, some of which most certainly resemble Earth.

If another Earth exists in the universe, wouldn’t it need to look like, well, Earth? Sure, but the odds of finding a blue world exactly 7,926 miles (12,756 kilometers) across and tilted on its axis nearly 24 degrees seem about as remote as finding an Elvis Presley impersonator who looks good in sequined leather and can snarl out a tune better than the King himself.

It doesn’t hurt to look, of course, and astronomers are doing just that. The idea isn’t necessarily to find an exact match, but a close one. For example, astronomers have discovered several so-called “super-Earths” — planets that are slightly larger than our home. Gliese 581g stands as a perfect example. It’s about three times the mass of Earth, which makes it a far better match than planets as large as Jupiter or Saturn.

In fact, behemoths like Jupiter and Saturn are known as gas giants because they’re nothing more than giant balls of hydrogen, helium and other gases with little or no solid surface. Gas giants, with their stormy, multicolored atmospheres, may offer spectacular sights, but they’ll never make good digs. Smaller planets, including Earth and super-Earth lookalikes, are much more likely to become incubators of life. Astronomers refer to these pipsqueaks as terrestrial planets because they possess heavy-metal cores surrounded by a rocky mantle. Terrestrial planets tend to stick close to their host stars, which means they have smaller orbits and much shorter years.

Terrestrial planets are also more likely to lie in the Goldilocks zone. Also called the habitable zone or life zone, the Goldilocks region is an area of space in which a planet is just the right distance from its home star so that its surface is neither too hot nor too cold. Earth, of course, fills that bill, while Venus roasts in a runaway greenhouse effect and Mars exists as a frozen, arid world. In between, the conditions are just right so that liquid water remains on the surface of the planet without freezing or evaporating out into space. Now the search is on to find another planet in the Goldilocks zone of another solar system. And astronomers have a couple of tricks they’re not afraid to use.

Creators of mankind

Creators of mankind Description of “Tall white aliens”

Description of “Tall white aliens” Where they came from?

Where they came from? About hostile civilizations

About hostile civilizations The war for the Earth

The war for the Earth “Tall white aliens” about eternal life

“Tall white aliens” about eternal life Video: “Nordic aliens”

Video: “Nordic aliens” Aliens

Aliens Alien encounters

Alien encounters The aliens base

The aliens base UFO

UFO Technology UFO

Technology UFO Underground civilization

Underground civilization Ancient alien artifacts

Ancient alien artifacts Military and UFO

Military and UFO Mysteries and hypotheses

Mysteries and hypotheses Scientific facts

Scientific facts