China has landed its first rover on Mars — here’s what happens next

China’s Tianwen-1 spacecraft, in orbit around the red planet, has dropped its lander and rover — named Zhurong after a Chinese god of fire — completing the most perilous stage of its ten-month mission.

According to Chinese state news agency Xinhua, an entry capsule enclosing the vehicles separated from the orbiter at about 4 a.m. Beijing time on 15 May. After several hours, it entered Mars’s atmosphere at an altitude of 125 kilometres.

It then hurtled towards the surface at 4.8 kilometres per second, protected by a heat shield. As the probe closed in on Mars, it released a huge parachute to slow its progress, and then used rocket boosters to brake. Once it reached 100 metres above the Martian surface, it hovered and used a laser-guided system to assess the area for obstacles such as boulders before landing.

The craft’s plummet through the Martian atmosphere had to be performed autonomously. “Each step had only one chance, and the actions were closely linked. If there had been any flaw, the landing would have failed,” Geng Yan, an official at the Lunar Exploration and Space Program Center of the China National Space Administration (CNSA), told Xinhua.

‘Big leap for China’

This is China’s first mission to Mars, and makes the country only the third nation — after Russia and the United States — to have landed a spacecraft on the planet. The mission “is a big leap for China because they are doing in a single go what NASA took decades to do”, says Roberto Orosei, a planetary scientist at the Institute of Radioastronomy of Bologna in Italy.

Zhurong now joins several other active Mars missions. NASA’s Perseverance rover, which arrived on 18 February, is several hundred kilometres away from the landing site, and NASA’s Curiosity rover has been poking around the planet since 2012. Several spacecraft are also circling Mars, including the United Arab Emirates’ Hope orbiter, which also arrived in February. “The more the merrier on Mars,” says David Flannery, an astrobiologist at Queensland University of Technology in Brisbane, Australia.

Researchers say that the engineering feat of getting there has taken precedence over science in China’s first tour of Mars, but the mission could still reveal new geological information. They are especially excited about the possibility of detecting permafrost in Utopia Planitia, the region in the northern hemisphere of Mars where Zhurong has landed (see ‘Landing site’).

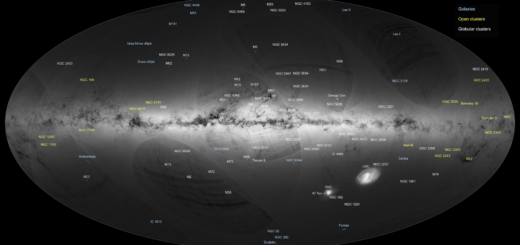

LANDING SITE. Map showing the landing site of the Chinese rover Zhurong as well as previous missions that have landed on Mars.

Biggest test yet

The Tianwen-1 mission included an orbiter, a lander and a rover — making it the first to send all three elements to the planet. The spacecraft departed Earth in July 2020 and arrived at Mars in February 2021, but the landing was the biggest test yet of China’s nascent deep-space exploration capabilities.

Landing on Mars is notoriously difficult, not least because engineers back on Earth have no control over it in real time, and must leave pre-programmed instructions to play out. Many missions have been lost, or have crashed on arrival.

In 1997, NASA’s Mars Pathfinder sent its first rover, named Sojourner, to a rocky region of the planet. “We didn’t get a lot of amazing science from that mission, but it paved the way for much more capable autonomous rovers, and now we are reaping the benefits of those missions,” says Flannery, who works on Perseverance, NASA’s fifth Mars rover.

What to expect

Within days, the six-wheeled solar-powered rover will trundle off the lander to explore for at least three months — but it could survive for years, as NASA’s Spirit and Opportunity rovers did.

Utopia Planitia, where Zhurong now sits, is a wide, flat expanse in a vast, feature-less basin that formed when a smaller object smashed into Mars billions of years ago.

The basin’s surface is mostly covered in volcanic material, which could have been modified by more-recent processes, such as the repeated freezing and thawing of ice. Orosei says that studies of the region from Mars’s orbit suggest that a layer of permafrost could be hiding just below the surface.

In 1976, NASA’s Viking 2 mission also landed on Utopia Planitia, but farther north of where Zhurong has touched down. “It’s a good place to try a first landing,” Flannery said before the landing. The low altitude, clear terrain and potential for finding ice in the subsurface also means that future missions might be able to collect samples there, and that the region could make a good landing site for crewed missions, he says.

ZHURONG. Graphic highlighting equipment carried by the Chinese rover to survey the geological structures on Mars.

Measuring Mars

Zhurong is kitted out with a suite of instruments for exploring the Martian environment (see ‘Zhurong’). Two cameras are fitted on a mast to take images of nearby rocks while the rover is stationary; these will be used to plan the journeys that it takes. A multispectral camera placed between these two navigation imagers will reveal the minerals present in these rocks.

Like Perseverance, Zhurong has ground-penetrating radar. As it winds its way across the basin, this will reveal the geological processes that led to the formation of the regions through which the rover travels. With luck, Zhurong might detect the thin horizon that marks any permafrost, says Orosei. Knowing how deep this lies, and its general characteristics, could offer insights into more recent climate changes on Mars, and reveal the fate of ancient water that could have once soaked the surface, he says.

If the researchers are really fortunate, they might even find some very ancient rocks, which could offer a window into our own planet’s history, says Joseph Michalski, a planetary scientist at the University of Hong Kong: most of the similar evidence here on Earth has been destroyed by plate tectonics, says Michalski.

Zhurong’s spectrometer includes a laser-based technology that can zap rocks to study their make-up. It will also be the first rover equipped with a magnetometer to measure the magnetic field in its vicinity. The instrument could provide insights into how Mars lost its strong magnetic field, an event that transformed the planet into a cold, dry place, uninviting to life.

A high-resolution image of the surface with a crater on Mars captured by China’s Tianwen-1 probe

A crater on the surface of Mars, captured by China’s Tianwen-1 orbiter.Credit: CNSA/Xinhua/Alamy

Orbital insights

From orbit, Tianwen-1 will communicate Zhurong’s insights to Earth. But the orbiter — the name of which means ‘questions to heaven’ — will also make its own scientific contributions with its seven instruments, including cameras, ground-penetrating radar and a spectrometer.

A magnetometer and particle analysers will study the boundary between the higher Martian atmosphere and solar winds to better understand how Mars’s magnetic field operates today. Combined with data from other orbiters studying the planet’s upper atmosphere, this knowledge will offer researchers “a much better picture of what goes on around Mars”, says Orosei.

A successful Mars landing could usher in more-advanced Chinese missions — including a sample-return initiative, which is planned to take place by 2030.

Creators of mankind

Creators of mankind Description of “Tall white aliens”

Description of “Tall white aliens” Where they came from?

Where they came from? About hostile civilizations

About hostile civilizations The war for the Earth

The war for the Earth “Tall white aliens” about eternal life

“Tall white aliens” about eternal life Video: “Nordic aliens”

Video: “Nordic aliens” Aliens

Aliens Alien encounters

Alien encounters The aliens base

The aliens base UFO

UFO Technology UFO

Technology UFO Underground civilization

Underground civilization Ancient alien artifacts

Ancient alien artifacts Military and UFO

Military and UFO Mysteries and hypotheses

Mysteries and hypotheses Scientific facts

Scientific facts